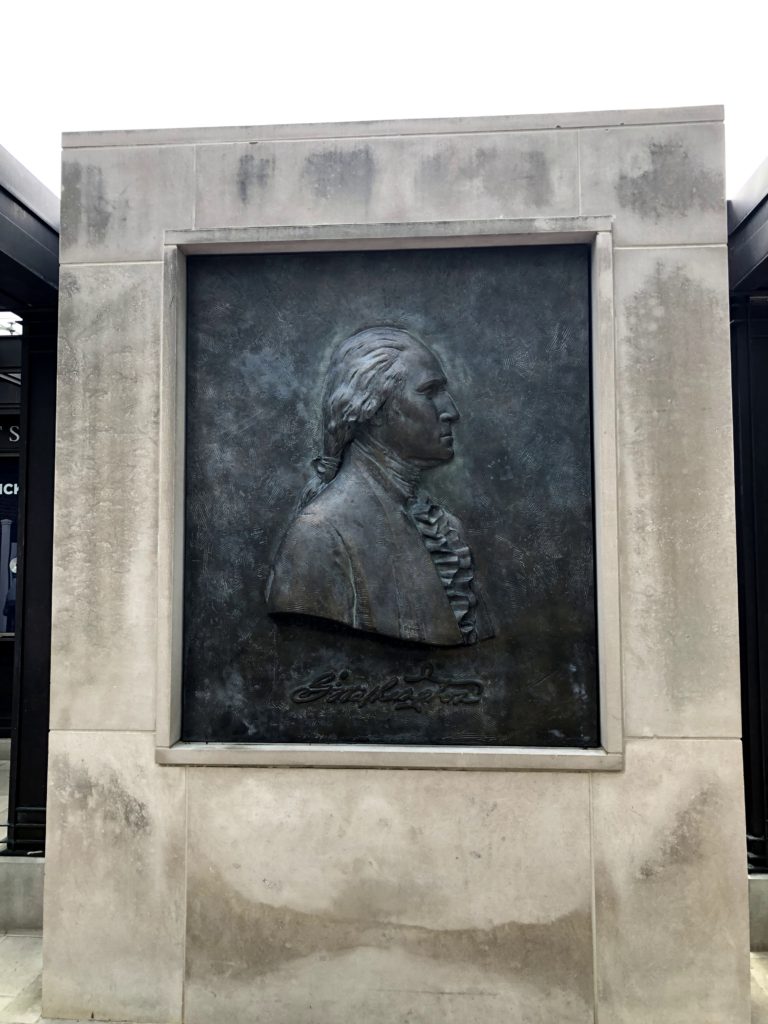

Sheep Shearing at Mount Vernon

Sheep shearing isn’t the only reason to visit George Washington’s Mount Vernon. This estate sprawls over 500 acres in Virginia, just south of Washington, DC. Once the home of George Washington, it is now a preserved historic area, boasting farms, gardens, tombs, and even a working mill. We’ve visited several times, but today I’m here for the sheep shearing!

Mount Vernon is a common field trip destination for the surrounding area. It is impossible to see everything in a single day, so visitors must prioritize or buy a multi-day ticket. With seasonal exhibits, you can revisit a few months later and see something new.

Mount Vernon is open 365 days a year! The mansion, shown here across the bowling green, was even open during refurbishment.

Plantation life included seasonal work, so visiting Mount Vernon during different times of year will ensure you see all it has to offer. My favorite time to visit is the spring because that’s when sheep shearing happens at Mount Vernon.

The crops have been planted and are starting to sprout, forming tidy little dotted lines across the field. Flax, hemp, and cotton were all grown for cloth and rope and you may be able to find demonstrations with those throughout the year.

My favorite part of spring, though, is the shearing of the sheep! In Washington’s time, the sheep in his flock numbered as many as 1,000! It took migrant workers a week to shear this flock by hand.

The fleeces were turned over to the enslaved people of Mount Vernon, who cleaned, carded, and spun the wool. This enabled Washington to clothe the enslaved population of the estate without importing cloth from overseas, which was growing increasingly more difficult and was costly.

Historical interpreters at Mount Vernon demonstrate the traditional methods of shearing sheep, dyeing wool, spinning fiber, and weaving cloth at the pioneer farm and spinning house.

The Sheep of Mount Vernon

Hog Island sheep are a special breed that live at Mount Vernon. I learned all about them at the Maryland Sheep & Wool Festival!

When colonists arrived on Hog Island, one of Virginia’s barrier islands, they brought sheep of various English breeds with them. Without fear of predators, the sheep roamed freely.

Conservation efforts to move the sheep started in the 1970s. Now they mostly live at historic sites that are better able to care for them. Hog Island sheep are still listed as critically endangered by The Livestock Conservancy. About 70 of the remaining 200 animals of this breed are located at Mount Vernon.

Some smaller farms maintain Hog Island sheep as well.

Sheep Shearing at Mount Vernon

Sheep shearing demonstrations occur in May. When we last visited, the shearing occurred twice daily on Fridays, Saturdays, and Sundays.

I loved that the interpreter used the same type of manual shears used in Washington’s time (Burgon & Ball). It is the type of detail that makes Mount Vernon a special experience. The shape of these shears creates a natural spring, but still, the work of shearing looks difficult and tedious. I imagine it requires a lot of hand strength.

The shearing took around 30 minutes. Less cooperative sheep seemed to take longer, perhaps because the livestock handler had to address several questions about the comfort of the sheep during the process. Shearing does not hurt; it’s the equivalent of a haircut… which would still be difficult to give to someone who didn’t want it!

After the shearing, this sheep also had his hooves clipped, the equivalent of a nail trim for us.

She wiggled a bit at first. When she realized she wasn’t in danger, she eased up a bit and let the historical interpreter finish her work.

The desired end result of this process is a whole fleece.

The next step is to clean this fleece so it can be carded and spun.

Fleece, Fiber, Fabric

Heading down toward the Potomac River, you’ll find women in a hut just east of the shearing demonstration.

Working adjacent to the sheep pen, they spend their days cleaning, carding, dyeing, hand spinning, and even knitting with Hog Island wool.

The cleaning involves hand-picking debris, then washing in very hot water with a solvent.

After she cleaned and dried the wool, she showed us how to card it. This process is similar to brushing with two wire-bristle brushes (like those for pets), pulled parallel in separate directions.

The result is that all of the fibers face the same direction, priming them for spinning. The process is simple, but takes time. Even practiced carders can only work with small amounts of wool.

Yes, they’ll even let your little ones have a turn!

After carding, wool is ready to dye.

Vibrant dyes like the ones pictured below wouldn’t have been purchased for slaves. Maybe you’ve heard of indigo, which provides the various shades of blue in this yarn and fabric. It was a costly import. (South Carolina and Georgia would go on to grow indigo during Washington’s time, but it was still a luxury.)

The red yarn to the far left was dyed with cochineal, a dye extracted from insects, and likely would have been imported, too.

It’s possible that some of these dyes could have been used by the slave population at Mount Vernon. Onion skins, for example, are an easily accessible source of dye.

Alum (the white powder pictured in the foreground) is not actually a dye; it’s a mordant. It caused the dye to “fix” to the fiber, preventing it from coming off of the fibers during regular wear and washing.

Gift Shop Finds

The gift shop was full of practical finds, including spinning and felting kits.

There were also adorable Hog Island sheep stuffies!

Plan Your Visit

George Washington’s Mount Vernon

3200 Mount Vernon Memorial Highway

Mount Vernon, Virginia 22121

website

2 Comments

Pingback:

Pingback: